In a small upstairs room of a Toledo church, Del Ray Grace is preserving a sacred piece of his Pentecostal upbringing. It isn’t an altar or a cross – it’s a steel guitar.

Starting in the 1930s, the instrument became the sound of worship in branches of the Church of the Living God, shaping a gospel tradition known as “sacred steel.”

Grace, a musician and archivist, has played the steel guitar for more than 50 years. In the last decade and a half, he’s built an archive around the music: gathering instruments, honoring standout players and preserving recordings of its electric cry, which bends and wails to the rhythm of the sermon.

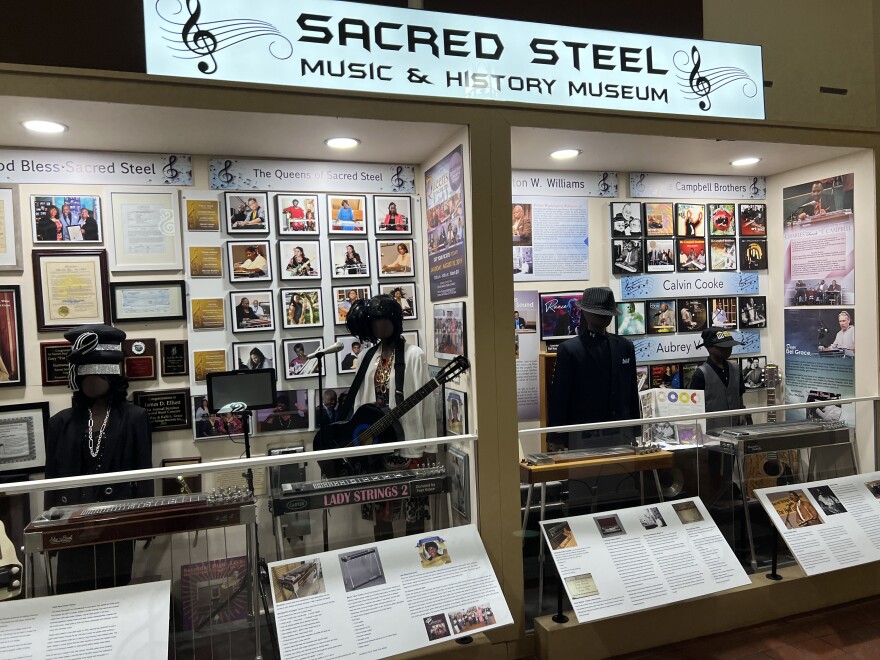

Last year, Grace opened the Sacred Steel Music and History Museum, the one of few repositories dedicated to the African American gospel tradition.

“In most African American churches, the piano and the organ are the lead instrument,” Grace said. “[The Church of the Living God] is probably the only church in America where that's not true. The steel guitar has established itself over the years as the lead instrument.”

‘Who’s on the Hawaiian?’

The steel guitar is as important to some branches of the Church of the Living God as the preacher giving the sermon, Grace said.

“The steel guitar player, he was like the equivalent to a rock star.”

But, before it found its sacred spot among the church pews, the instrument originated in Hawaii. Its sliding tones were a key feature in odes to the Pacific island and became commonly known as the “Hawaiian guitar.”

The instrument soon made its way to the mainland. Country musicians adopted it, and so did Truman Eason, a follower of the Church of the Living God.

“He began bringing it into the church, so it started to catch on,” Grace said. “Little Johnny, little Sue, little Del Ray, we start to see these guys and say, ‘I want to do that.’ Here we are, almost 90 years later.”

‘A language we speak’

On a September afternoon, Grace grabbed one of the guitars from a small stage set up in the museum. The simple yellow instrument stretched across his lap, lying face-up. That makes it easier to pick between the strings, he said.

“It takes a lot of practice. It’s not an easy instrument by any means.”

In one hand, he held a steel bar across the frets, allowing the guitar to slide effortlessly between notes, giving it its signature wail. In the other, he wore a couple of plastic picks that plucked out the chords to “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

“It's a language that we speak. We teach this by oral tradition,” he explained. “You can't go to the Juilliard School of Music and all that and say ‘I want to learn sacred steel.’ It's not there. You have to be in this environment. You have to be in these churches.”

During church services, people often stand and clap along to the whining tone of the guitar. The congregation sways with the music, which soars to an ecstatic peak during steel guitar solos, performed by veterans like Grace.

Each time he plays, Grace said it’s a spiritual experience.

“This music is given to us by God, so you're constantly getting downloads as you go, and a lot of times you have to go back and listen, because people say ‘Man you played this, you played that,’ and you're like, ‘I did? I was in the spirit at the time.’ ”

‘A musical force’

Grace wants the genre to be recognized by more than just members of his church. That’s what led him, in 2009, to begin piecing together the history of sacred steel.

Today, his museum features an archive room with documentaries and interviews, exhibits highlighting women in the church, a wall with Hall of Fame performers and the stories of their musical accomplishments.

He urges all sacred steel performers to document each time they play.

“A lot of these guys are finding themselves getting calls. Some of these guys have been on soundtracks of motion pictures and things like that,” Grace said. “I want it to be recognized as a musical force, a musical genre. Because I think it's just as powerful, if not more so.”

Too often, he said, the news is saturated with negative stories about the African American community. To him, the story of sacred steel, and the performers that have carried the genre forward, is far more worth passing down.

“I did not want to die with this story inside of me, like so many people,” Grace said. “I want the world to know that great men and great women walked this way, playing this music for the Kingdom of God.”